Chapter 3 Open source, open licencing, scientific programming

3.1 Open-source

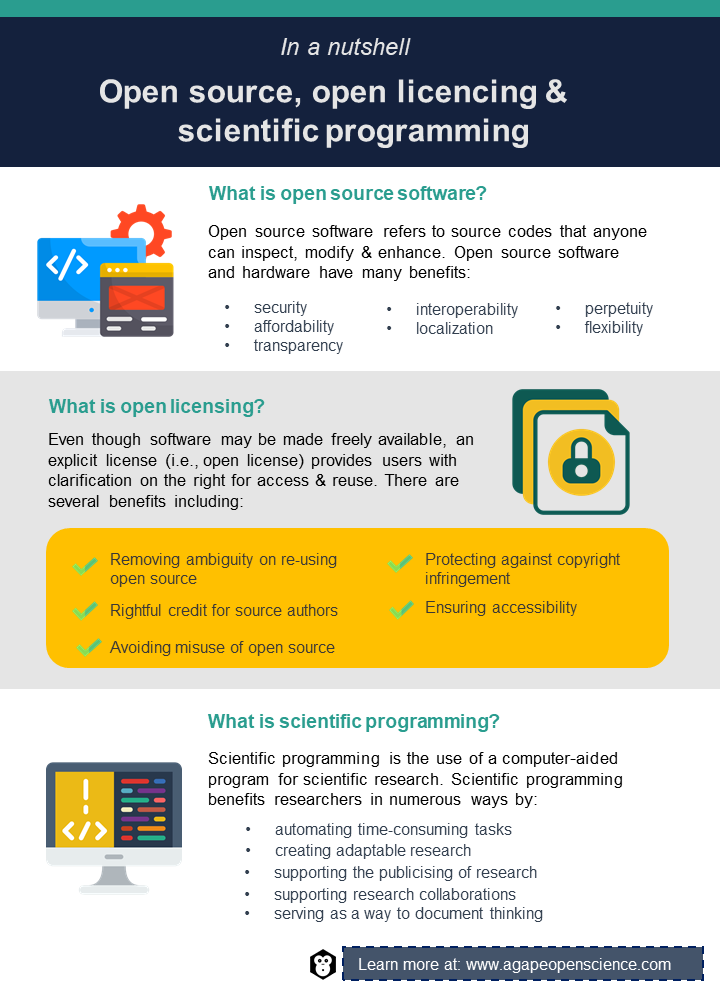

It is no secret that the open science movement got its inspiration from the open-source culture movement. Open-source software refers to source code that anyone can inspect, modify and enhance because the licence under which it is released grants permission to do so. You can find a more detailed definition on the website of the Open Source Initiative. Similarly, Open Source Hardware Association defines open-source hardware as “hardware whose design is made publicly available so that anyone can study, modify, distribute, make, and sell the design or hardware based on that design.”

The main benefits and reasons for the adoption of open-source software and hardware (Casson and Ryan, 2006) can be categorised as follows:

- Security

- Affordability

- Transparency

- Perpetuity

- Interoperability

- Flexibility

- Localization

3.2 Open licensing

Even when your data, software or hardware design are made freely available in the public domain, an explicit licence would provide legal clarity on the access and re-use of it. You can licence the data only if you are the rightful owner. Licensing helps to:

- Remove the ambiguity on the re-use of data

- Exempt users from copyright infringement

- Ensure that the source author is credited rightfully

- Ensure that the re-used or re-distributed data remain open access

- Ensure that data is not misused or distorted

How to choose a licence

- Ensure that the data is copyrightable. This may vary across domains, jurisdictions, funders, etc.

- Check the licensing obligation of the funder(s), institution(s), government, data centre or repository.

- If your work is a derivative of a third-party author, ensure to comply with the source data’s licensing requirements.

- Select the data licence with the conditions that meet your criteria and that covers the content that you want to share.

The most common conditions found in data licences are:

- Attribution (BY): The source/author must be acknowledged when it is distributed, displayed, performed or used to derive a new work. If you are using data from multiple sources, each contributor needs to be acknowledged.

- Copyleft or share alike (SA): Any new work derived from the licensed data should be released under the same licence of the source data.

- Non-commercial: This type of licence prevents the user from using the data for commercial purposes.

3.3 Licence providers

Prepared licence: Research Institutions or other data publishers can create licences. For example, the UK Data Archive requires that you sign a standard licence agreement that clarifies the rights and responsibilities of both parties and permits the UK Data Archive to perform its curatorial function.

Bespoke licence: If the existing licences don’t meet the author’s requirement or cater to special circumstances, they can make their own licence. In this scenario, it is mandatory to ensure that the custom licence complies with any existing legal bindings.

Creative Commons: One of the most popular and widely accepted licence providers for most content with the exception of source code. Three versions (CCO, CC-BY, CC-BY-SA) of it are intended for open licensing. Choose a licence by GitHub provides a list of licences that are specific to software codes.

Open data commons: Similar to Creative Commons, but these licences are specifically designed for databases.

3.4 Scientific programming

Documenting your code

To make your research open, i.e. transparent and reproducible, it is good practice to share not only your data but also the code used for the analysis, modelling, visualisation, etc. This code is then known as open-source research software. When sharing your code or software, it’s good practice to also include documentation explaining how to use your code. So why do you need to prepare this documentation?

Benefits for you:

- In six months’ time or whenever you choose to work on it, you’ll still be able to use your code.

- You want people to credit you when they use your code.

- You want to learn how to be self-reliant

- You may attract others to contribute to your code. Benefits for others:

- Others can simply utilise and extend your code. Benefits for science:

- You are contributing to science.

- You are promoting open science.

- Documentation allows for clarity and reproducibility.

Here are best practices for writing documentation:

Provide a README file with the following information:

○ A quick overview of the project

○ Instructions for installation

○ A brief example/tutorial

Allow others to use the problem tracker.

Create application programming interface (API) documentation.

Write down your code.

Use coding conventions, including file structure, comments, naming conventions, programming methods, etc.

Include an introduction for contributors.

Provide citation information.

Include any licensing information.

Include a link to your email address.

List all the file versions and the fundamental changes you made.

A helpful hint: When naming files, make sure their names are descriptive and consistent!

Importance of scientific programming

There are multiple ways in which scientists and researchers can benefit from scientific programming. Scientific programming significance includes a wide range of abilities without focusing on any particular field. Generally, scientific programming can facilitate the following:

- Time-consuming tasks can be automated – Automating tasks using scientific programming can simplify long-term tasks or those that are impossible to do by hand. Imagine, for example, that you want to figure out how many tweets were posted about a recent natural disaster and you have to sift through tens of thousands of feeds one by one. A few minutes might be enough to complete this task with code.

- Creating adaptable research – You can modify and rerun your code repeatedly if you write it correctly. Consider you are researching the relationship between socio-economic data and air pollution in a particular location. Using a properly structured and well-commented script, updating each year’s socio-economic data can be easily incorporated.

- Help to publicise the research and share the findings with other researchers – Because code is so easily accessible, research becomes more open and repeatable. It helps the researcher to convey their specific methodology to other experts as well as the community.

- Documenting your thinking – You can quickly document your strategy with code. You may use comments to describe each stage of the process (to your future self or others), making it quick and easy to update or adjust things afterwards.

- Research collaboration – Collaboration is facilitated by the use of code. Returning to the previous example, if you are researching air pollution in a particular location and a colleague is researching air pollution in another location, you may compare models, swap scripts and collaborate.

The above five features of scientific programming assist the researcher significantly in various ways and are considered key tools to nudge research forward. The significance can be simply identified by the speed of conducting the research through a high level of computation and, most importantly, the collaboration and the modifications that may apply. Scientific programming has been, and continues to be, ground-breaking. From assisting biologists in sequencing the human genome to allowing social scientists to make better economic forecasts the applications are limitless.

What exactly is scientific programming?

There is a simple definition of scientific programming, yet it covers a vast array of applications and industries. Using a computer-aided program for scientific research is referred to as science programming. Scientific programming can be useful for most scientists and researchers, especially PhD researchers. The rate and reproducibility of a researcher’s work can be exponentially increased using scientific programming. Computers, designed for efficiency and scale, can perform massive calculations, store data and analyse results. By automating processes, scientists are able to save time and effort and make research more accurate, reliable and efficient.

It is essential to note that computers are error-free when it comes to mathematical processes. Occasionally, mistakes can happen, but these mistakes usually occur because people make errors when using computers. Computers follow directions, so if a calculation goes wrong, the computer will not understand it independently. However, a computer can do calculations within minutes that would take researchers months or even years to perform. Furthermore, the code will execute the calculations consistently for each run.

Respond to disasters: an example of the power of scientific programming

In addition to its many advantages, scientific programming can accomplish a great deal of work that would be impossible for one person or even a team of people to complete without it. Lise St. Denis’s research on climate change at Earth Lab demonstrates that power clearly. Lise uses Twitter to notify first responders about emergency situations that result from natural disasters as they develop or progress. Without this technology vital time sensitive information may be missed.

In the event of a disaster, the police are contacted alongside emergency services. Disaster survivors also reach out to their online communities, sometimes providing vital information. The call volume of hotlines during disasters can be overwhelming for authorities and the only way for people to communicate may be through social media. Thus, sites like Twitter can be a great source of information for disaster response teams. However, the volume of tweets makes it difficult for one person (or team) to vet all the information and still get it to emergency response teams in time. Lise St. Denis witnessed this through her extensive experience of natural disasters. For instance, during the Carlton complex fire of 2014, she worked on a team that was tasked to sort tweets and compile a full report. Although Lise’s team provided useful information, it was unable to keep up with the volume of tweets and responders needed the information faster than the team was able to provide it. For Lise, the answer was obvious, they needed to deploy the superpowers of scientific computing.

Since the beginning of 2013, Lise had been developing a filtration algorithm to harvest data from Twitter and sort it by importance. Using this code, one person can automate the work of a whole team of humans by analysing and categorising every single tweet as they arrive. As a result of the algorithm, tweets are separated into those which first responders need to know about and those which the algorithm deems as less important. One of scientific programmings’ capabilities is the ability to “look” at enormous amounts of rapidly generated data and categorise it.

The future of scientific programming

Because there are so many fascinating possibilities, it is difficult to pick one field of scientific programming that is remarkably promising. Almost every discipline of study has a programming tool that could be considered as the “future of programming” and it would be difficult to discuss and list them all.

Modelling is a promising development that serves multiple professions. For decades, models have served as the foundation of science. There are a wide range of examples of using modelling techniques in science, ranging from Earth science (predicting wildfires) to medicine (analysing illnesses). No model is perfect. Thus, there is continuous development in the pursuit of better, more precise models with complete algorithms producing reliable results.

In today’s data-driven world, the term science is closely linked with scientific programming. Problems that have baffled scientists for decades are addressed in a matter of seconds by leverage the power of large computers. The rise in efficiency and speed has completely transformed most sectors of modern science. Without question, scientific programming is our way forward. To be part of this movement, you can share your code with others and always appropriately cite the open source you use.

3.5 Test your understanding

Activities

In a recommend activities section like this one, we will recommend the activities to increase your understanding of the concepts and improve your practical knowledge.

Learn more about open-source software and hardware on Open Science Training Handbook or try to work on a DIY open-source hardware project.

Have you ever checked licences on the types of software you are using? Now is the time to do that. Is the software you are using open-source software?

Working on your research project can be exhausting at times. Why don’t you try relaxing and practice open-source software skills by playing some of the following games? Play and learn!

○ CodeCombat: These games take you step by step through ideas, starting with basic computer science and gradually increasing in difficulty.

○ CodinGame: When you have a better grasp, this game is about solving challenges in specific languages.

○ CodeWars: Get right into programming challenges and experience debugging your code.

Have you ever shared your code, worked on an open-source hardware project or do you have any other experience related to this chapter? Share it with others on our social media.