Chapter 1 Open science

Let’s start at the beginning.

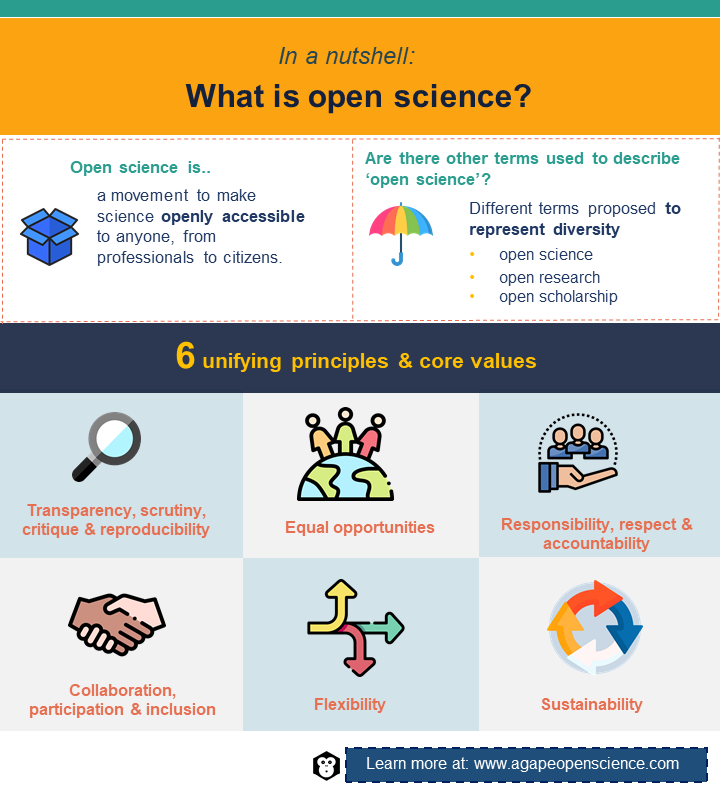

Open science is a movement to make scientific research, data and their dissemination available to any member of an inquiring society, from professionals to citizens.

Open science comprises several themes from conception to dissemination of knowledge. Based on principles of scientific growth and public access, open science includes practices such as open publishing and campaigning for open access, with the ultimate aim of making it easier to publish and share scientific knowledge.

1.1 What is open science?

Open science refers to a vision to improve scientific practices for reproducibility, transparency, sharing and collaboration of knowledge. Multiple pathways to achieving this vision have developed since the concept emerged in 1985 (Chubin, 1985).

As part of the global open science community, we expand the term “science” beyond its common use, such as life sciences or engineering, to include the arts, humanities and any other scholarly activities. Open science, open research and open scholarship are often used interchangeably. For consistency and ease of understanding, we use open science in this course.

1.1.1 Open science = open research = open scholarship

Generally, the open science movement identifies increased openness of scientific content, tools and processes as the key means of action. However, a single definition cannot encompass the diversity of the open science movement. Therefore, we give some alternative definitions of the phrase open science throughout this chapter.

The first definition we review is from the European FOSTER project. According to the FOSTER team, “open science is the practice of science in such a way that others can collaborate and contribute, where research data, lab notes and other research processes are freely available, under terms that enable reuse, redistribution and reproduction of the research and its underlying data and methods.” This definition highlights that open science is the act of improving access and contribution to all aspects of scientific practice: from research design, methodologies and tools, generated data, reporting and evaluation.

In an attempt to capture the complexity of open science, Fecher & Friesike (2014) define it as “an umbrella term encompassing a multitude of assumptions about the future of knowledge creation and dissemination”. The authors summarise the movement complexity by identifying five schools of thought. Namely, the democratic school (concerned with knowledge access), the public school (concerned with accessibility to knowledge creation), the measurement school (concerned with alternative impact measurement), the infrastructure school (concerned with the technological architecture of science) and the pragmatic school (concerned with collaborative research). This (somewhat arbitrary) separation highlights the various paths in which science can be “opened”.

Based on a review of published definitions and information Vicente-Saez and Martinez-Fuentes (2018) concluded that “open science is transparent and accessible knowledge that is shared and developed through collaborative networks”. Here, knowledge includes code, data, ideas, information, scientific outputs, scientific publications and scientific results. Paic (2021) identified emerging trends in open science such as alternative reputation systems, open notebooks, open lab books, science blogs, collaborative bibliographies, citizen science and open peer-review.

Another definition we would like to present is the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) definition. Drafted at the 40th UNESCO General Conference in 2019 and officially published in 2021, the Recommendation on Open Science contains the following statement: “For the purpose of this Recommendation, open science is defined as an inclusive construct that combines various movements and practices, aiming to make multilingual scientific knowledge openly available, accessible and reusable for everyone. It also aims to increase scientific collaboration and sharing of information for the benefit of science and society and to open the processes of scientific knowledge creation, evaluation and communication to societal actors beyond the traditional scientific community. It comprises all scientific disciplines and aspects of scholarly practices, including basic and applied sciences, natural and social sciences and the humanities and it builds on the following key pillars: open scientific knowledge, open science infrastructures, science communication, open engagement of societal actors and open dialogue with other knowledge systems.”

Here, the UNESCO members clarify the meaning of the term science to include the humanities and the liberal arts. Furthermore, this definition highlights how the open science movement broadens its areas of influence beyond general research practices to the researcher community and society at large. The movement thus aims to better the inclusion of diverse ethnicities, cultures, languages, backgrounds and availability of resources across the scientific community.

Lastly, The Turing Way Community (2021) illustrates open research and its subcomponents as fitting under the umbrella of the broader concept of open scholarship in their handbook on reproducible, ethical and collaborative data science. These subcomponents are open data, open-source software, open-source hardware, open access, open notebooks, open educational resources, citizen science, equity, diversity and inclusion.

Many other definitions of open science can be found on-line or within written records. However, in consolidating the mentioned sources together, we conclude that six unifying principles and core values characterise the open science movement. These are:

Transparency, scrutiny, critique and reproducibility

Equality of opportunities

Responsibility, respect and accountability

Collaboration, participation and inclusion

Flexibility

Sustainability

1.2 The history of open science

Previously, we mentioned the vision and principles the open science movement shares. To better understand the implications opening science might have, it is useful to appreciate how the contemporary values and principles of both science and open science came to be. As Watson (2015) suggests, science is easily perceived as already “open”, as already belonging to everyone. However, contemporary science is much more recent than one may think and its organisation has greatly transformed over the last 500 years. Even the current dominant practices of science are not immutable and they are likely to continue to change again in the future, evolving within the broader context of society.

1.2.1 17th to 20th century: The emergence of contemporary science

“For in the sciences the authority of thousands of opinions is not worth as much as one tiny spark of reason in an individual man.”

– Galileo Galilei, ca. 1597

Between the 17th and 20th century, science underwent multiple reformations. If you were to meet scientists from before the 17th century, their perception of science would probably shock you. For centuries, they had more or less accepted the authority of the Church and of monarchs and their claims and theories didn’t need to be backed up with either observable proof or the proof of reason. During the reformation, profound advancements in science took place and the scientific community gradually adopted scientific publications, formal review processes, scholarly associations, public grants and many more of the common modern practices.

The advent of printing and publishing companies in the early 17th century made public libraries more and more common. Knowledge started to accumulate in printed reports and encyclopaedias and, for the first time, it became accessible to the general public. At the time, this meant mostly privileged male and white citizens with greater socioeconomic resources and greater perceived standing in the social hierarchy.

During the same period, scholars started to move from unstable aristocratic patronages to assembled academies of science, slowly adopting academic publishing. Merton (1963) tells us that between the 1650s and the 1850s, the number of simultaneous discoveries ending in disputes dropped from 92% to 33%. Cryptic monographs and academic duels slowly became a thing of the past and science gradually became more open.

“The assumption that peer review is as old as journal publishing […] is based on a misunderstanding of Philosophical Transactions’ editorial practice. […] Indeed, for most of the history of scientific journals, it has been editors – not referees – who have been the key decision-makers and gatekeepers.”

– Aileen Fyfe, 2015

After the establishment of scientific publishing and academic societies, the development of a formal review process developed between the 19th century and first half of the 20th century. We might take today’s practice of peer-review, in which one or more people with similar competencies (peers) as the author review a manuscript before publication on a voluntary basis, for granted. However, it took until the 1970s before peer-review became widespread. (Fyfe, 2015).

The first recognized formal review practice was implemented by the British Royal Society in 1832. A special committee within the society was responsible for accepting or rejecting submissions for publication based on independently written evaluations. George Gabriel Stokes, secretary of the Royal Society from 1854–1885, further refined this practice by sharing the referees’ suggestions with the authors and facilitating the discussion between authors and referees. Similar review processes started to become common practice in other academic societies across the world during the 19th century.

On the other hand, private publishers would only introduce formal review practices in the 20th century and the journal editor(s) were the sole judge of acceptance or rejection of a submission. These trivial selection practices allowed for a fast research-to-publication cycle, making private journals appealing for swift communication between scientists. At this stage, societies’ journals gradually hosted fewer and more refined publications, while private journals were the preferred communication channel between scientists.

1.2.2 Modern science and the fight for openness

As submissions grew in volume, private journals started to implement review practices in the second half of the 20th century, gradually bringing us to the current state of research practices. However, with private publishers flourishing, new economic and structural barriers to scientific knowledge arose. For example, nowadays a yearly subscription to a scientific journal can cost between 3,000 and 7,000 USD (Bosch et al., 2022) compared with much more affordable mainstream media subscriptions. For example, the New York Times offers a yearly subscription for 20 USD.

Much of today’s scientific publication is in the hands of five large publishing companies: American Chemical Society (ACS), Elsevier, Springer-Nature, Taylor & Francis and Wiley-Blackwell, who own 50 to 70% of the scientific writing market (Puehringer et al., 2021). A sentiment of anger is often apparent in scientific communities towards the private publishing sector. For example, Buranyi (2017) explains that “Scientists create work under their own direction – funded largely by governments – and give it to publishers for free. The publisher pays scientific editors who judge whether the work is worth publishing and check its grammar, but the bulk of the editorial burden is done by working scientists on a volunteer basis. The publishers then sell the product back to government-funded institutional and university libraries, to be read by scientists – who, in a collective sense, created the product in the first place.”

The roots of open science stem from philosophical discussions ongoing in the 1970s and 1980s about what it means to have freely available scientific knowledge and not in the fight for more just publication practices (Chubin, 1985). However, we believe that the struggle for open access publication spurred the rise of the open science movement, which then drew together all of the elements previously mentioned.

A second steppingstone in the history of the open science movement was the advent of the Internet. From its infancy, the Internet shifted how information is shared and facilitated new methods of scientific exchanges. Literature research moved from public libraries to online repositories such as the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) which was launched in 2003 with 300 open access journals. Scientists also began to share early versions of their work or pre-prints through servers such as Biorxiv. Furthermore, online collaboration facilitated easily accessible information resources such as Wikipedia which became a household staple. A new reformation of science had begun.

“The question is no longer whether open science is happening, but how everyone can contribute to it and benefit from this transition.”.

– Audrey Azoulay, Director-General of UNESCO, 2021

1.3 Test your understanding

Activities

In a recommend activities section like this one, we will recommend the activities to increase your understanding of the concepts and improve your practical knowledge.

When did you first hear about open science?

Propose one change you could bring to your workflow to implement one of the core values of open science presented.

Try to imagine how open science will change during your lifetime. And what about the 22nd century? What do you think the future of science will look like? Will it finally become fully open?

Share anything interesting that you learned or found in this chapter with others on our social media.